escape the sun

The Old World was drowning in its own scripture. Catholics and Protestants carved each other from Flanders to Bohemia, both sides claiming heaven’s favor while hell collected the taxes. Kingdoms rose and peasants bled in the mud as priests argued whose god shouted louder.

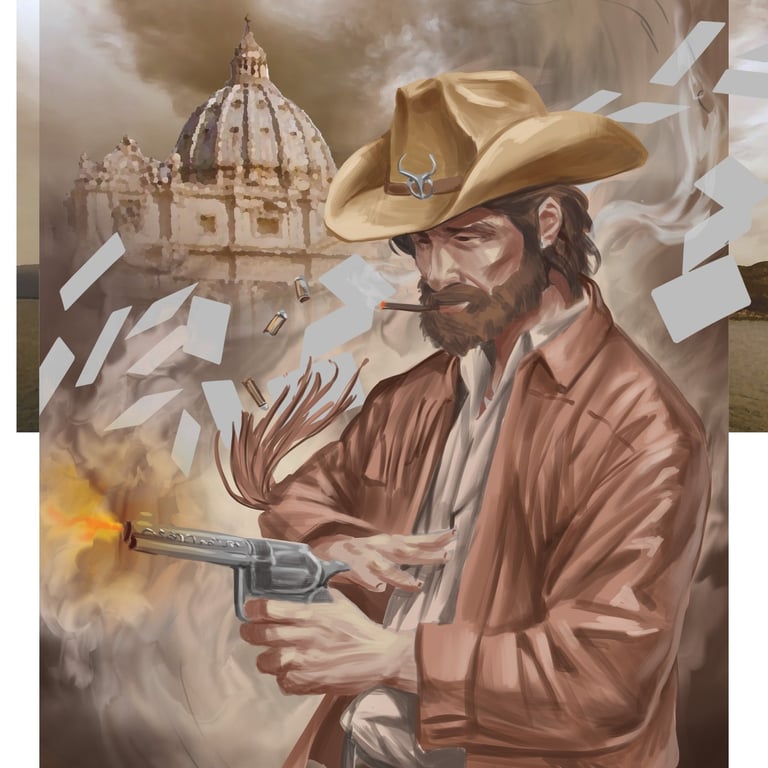

Across the ocean, the New World festered. Flags sprouted like weeds, with each empire planting a banner in soil that wasn’t theirs. Silver and pelts traded hands while the native peoples fought tooth and bone to keep what was left, sometimes with fire, sometimes with cunning.

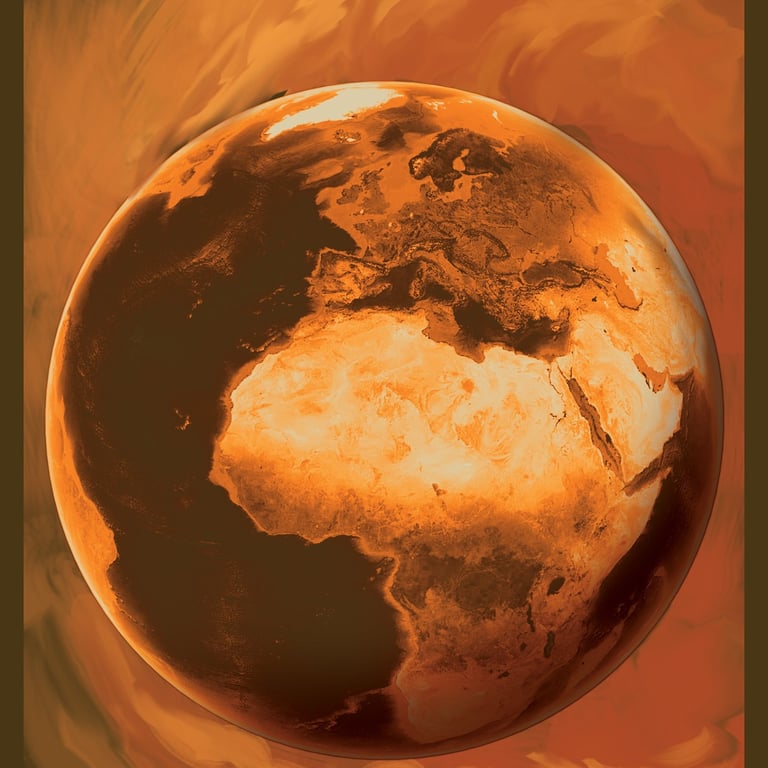

Europe barely noticed that the Sun God was getting hotter. Crowned heads were too busy cutting each other to ribbons in holy wars that promised glory and delivered famine. It was then that the sky turned cruel.

It started at the beginning of year 1607, in the Ottoman lands: a sun that wouldn’t cool, a summer that never broke. Wells dried, crops burned, forests vanished. By Christmas, even the Alps were naked.

Word drifted west with deserters and half-mad sailors, and soon the harbors of the Americas were filled with ghosts: galleons in rags, riverboats lost at sea, crews half-eaten by thirst and each other. Spaniards, Moors, slaves, heretics fled an Europe turned to dust in an endless tide of the damned.

Then came the last ship, on Valentine’s Day, 1608. It crawled into port like a floating coffin, stinking of salt and rot with only one thing that was still moving aboard: a swollen woman from the ruins of Southern Italy. She’d eaten crew and passengers, even the rats.

They shackled her in iron and hauled her to the scaffold. When the priest began the rites, she laughed and spat a line in her mother tongue:

“Un su muarti, si su ammucciati sutt’a terra.”

The executioner hesitated, then swung: her head rolled, and the crowd roared. He turned pale and whispered to the judge:

“They’re not dead. They’re underground.”

See how the world of the Weird Fronteira RPG takes shape through the art of our Illustrator